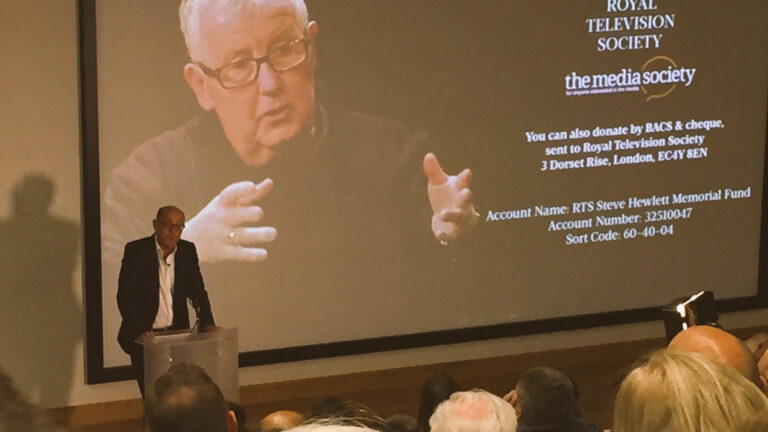

Nick Robinson paid tribute to Steve Hewlett as he delivered the inaugural lecture in the broadcaster’s name.

“Steve’s death was news – national news – which, had he been here to see it and to see you all gathered here for the first annual Steve Hewlett memorial lecture – would have produced one of those characteristically laconic Hewlett chuckles,” he said to the audience at the Media Society and the Royal Television Society, which included Hewlett’s family.

“It was news, of course, because millions had grown used to turning up the car radio or stopping the ironing or waiting before turning on the kettle to make sure they not miss the latest weekly instalment of the Hewlett cancer chronicle – in which a middle aged man described the pain in his oesophagus; the splitting of his nails or chapping of his feet; of the search for the drug or the treatment that might buy him some relief and some more time before the end which he sensed and we sensed was coming all too fast.

“’To cut a long story short’ was one of Steve’s catchphrases. His tales from the medical frontline – many of his tales – were, of course, anything but short and could, of course, be all too painful to listen to. Few would have imagined that they would be a recipe for broadcasting gold. Except, perhaps, for Steve. They were one last reminder of his sixth sense which meant he knew, he just knew, the stories that would engage an audience and, boy, did he know how to tell them.”

Robinson got to know Hewlett straight out of university. He joked that he was “as establishment as you could get” while Hewlett “carried the aura of radical chic” having come from Channel 4, where he managed to make a film combining his “two greatest passions” – a Marxist interpretation of cricket.

They would work together later in their careers as editor (Hewlett) and deputy editor (Robinson) of Panorama.

“What brought us closer, though,” continued Robinson, “was our shared experience of cancer. When I was recovering from the surgery which successfully removed my tumour but robbed me of my voice. Steve reassured me and wrote in the Radio Times that the audience would get used to my new throaty sound. When he told me about his diagnosis I wrote him a beginner’s guide on how to cope with chemotherapy. I still fondly recall the marathon cancer chat we had during a more than two hour drive from my home in London to the University of Essex to help open their new Journalism course. When I finally arrived and got Steve off the phone I realised I’d forgotten to talk to him about what I called him in the first place to discuss –journalism!”

Robinson used his speech to warn of the erosion of trust when it came to traditional news sources, with the rise of news via social media.

“We need to learn from Steve’s open minded willingness to challenge the conventional wisdom,” he explained.

“And to embrace a Mission to engage with those who do not treat news bulletins and current affairs programmes as ‘appointments to view’; those who don’t trust what they’re told and those who crave the tools to separate what is true and what is important from the torrent of half facts and opinion, prejudice and propaganda which risks overwhelming us all.”

He believes that this will mean finding new ways to ensure on air diversity, not just through gender, ethnicity and age, but also background.

Moreover, he said that the case needed to be remade for impartial news media.

“When Steve first became a journalist people had the choice of just three TV channels. There were no news channels, websites, blogs or social media

“[…] But you know all that. What you may not know is what the latest figures show. When those between 16 and 24 “watch” a broadcast they’re only watching on what their Mums and Dads would call “the telly” or ‘the Box” on just over a third of what the statisticians call viewing occasions

“More and more access news on their smartphones – almost a half whilst in bed, a little fewer on the bus or train and, wait for it, a third whilst on the loo. No wonder those same 16-24 year olds are watching less than half an hour of TV news a week – a fall of a third in under five years.

“To summarise a little crudely – fewer and fewer young people are watching news on TV.”

He quoted a meeting he had with the veteran journalist and now head of Google News, Richard Gingras

“We came from an era of dominant news organisations, often perceived as oracles of fact. We’ve moved to a marketplace where quality journalism competes on equal footing with raucous opinion, passionate advocacy, and the masquerading expression of variously-motivated bad actors,” stated Gingras.

“Affirmation is more satisfying than information. Always has been.”

Robinson used the example of Jon Snow and his experience when faced with angry residents of the Grenfell Tower. The fact that there’s now a decline in trust in the “MSM (mainstream media)” and the polarisation of society has led to increased use of social media alternatives.

He recalls his own experiences of Finsbury Park, when a van struck worshippers outside a mosque and he was confronted by a group of young Muslim men.

“Why – they demanded to know – are you not calling it terrorism? They showed me the BBC’s report which described a “collision”. So too, in fairness, did other mainstream sites like Sky News. I tried explaining that news organisations always waited for the police to determine whether an incident was an accident, an attack or, indeed, terror. They weren’t impressed. They thought we were on the side of those who wanted to cover up attacks on their community. They said they trusted their own media more.”

This he explained was a pattern that was steadily increasing:

“People who seen themselves as not part of the establishment – whether young Muslims, Scottish Nationalists or UKIP-ers, Corbynites or Greens, backers of Leave pre-referendum but, since the vote, backers of Remain – have not just complained about the coverage of what they increasingly refer to as the mainstream media or MSM. They have their own alternative media sites – Wings over Scotland or Westmonster or The Canary or – in the case of the pro EU crowd – a new newspaper – the New European.”

“They would all be horrified to be compared with each other since what motivates them is the belief that the other lot are not just mistaken but an existential threat to the future of their country but they have and do often respond in similar ways to what they call the mainstream media.”

He said that in politics, this thought process was now a key part of their strategy:

“When I interviewed Paul Mason – formerly a distinguished colleague at the BBC and Channel 4 – now a hyper partisan campaigner for Jeremy Corbyn he told me ‘we see the media as the enemy navy, we need our own navy.’”

Also attending the event was Oliver Cummins Hylton, the first Steve Hewlett scholar, who’ll study broadcast journalism at the University of Salford.

[Picture: @RTS_Now]