University of Sunderland researchers are backing Sir Chris Hoy’s calls for more prostate cancer screening for high-risk men.

The Olympic cycling champion, 48, who has terminal cancer, has urged men with a family history of prostate cancer to see their GP for a blood test even if they are under 50.

It comes as researchers at Sunderland have been working with members of the Black community in the North East and Scotland for the last two years to develop and run workshops to raise awareness of prostate cancer risks, encourage men to get help early and discover the barriers to seeking help.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in the UK, but Black African, Caribbean, and Black British men are twice as likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer compared to white men, and 2.5 times more likely to die from the disease.

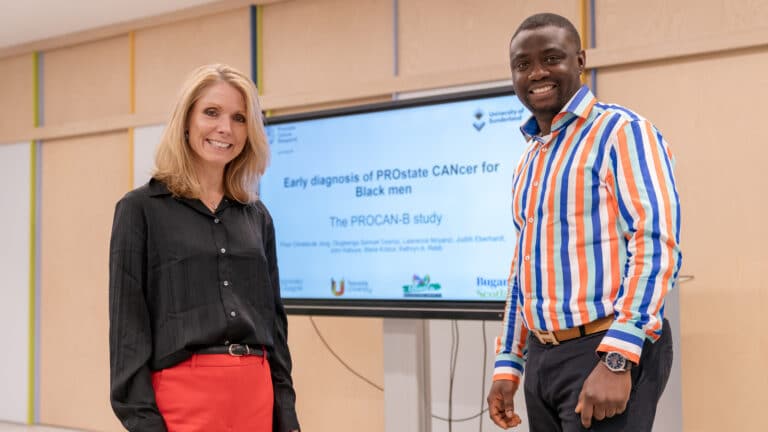

The study – Early diagnosis of PROstate CANcer for Black men (PROCAN-B) – was awarded £157,688 in funding as part of charity Prostate Cancer Research’s racial disparities research programme, aimed at addressing the health inequalities in prostate cancer.

The charity hosted an event at the House of Commons last week (Thursday 14 November) where they unveiled new data on the economic and health advantages of implementing a national screening programme for high-risk groups.

Dr Floor Christie-de Jong, Lead Researcher and Associate Professor in Public Health in the School of Medicine at the University of Sunderland, said: “Early diagnosis saves lives, yet we lack a national screening programme to catch prostate cancer early.

“I’m 100 percent supporting the efforts of Prostate Cancer Research and Sir Chris Hoy to drive a prostate cancer screening programme for men who are at higher risk, including Black men and men with a family history of prostate cancer, is urgently needed. Such a programme can save lives and play a key role in reducing inequalities in prostate cancer outcomes”.

As a first step in the PROCAN-B study, the research team asked 13 Black men from the North East and Scotland why they found it difficult to see a doctor for prostate cancer. Their reasons included not being fully aware of the risks of the disease, feeling uncomfortable talking about sensitive issues and having bad experiences with accessing healthcare, including racism.

Based on these findings, the researchers developed a workshop delivered by Black men for Black men, which featured small group discussions and activities, a Black GP explaining about prostate cancer and what’s involved in prostate cancer health checks, and videos from religious leaders and prostate cancer survivors.

The workshop was run with 62 men in total in the north-east and Scotland.

Data collected following the workshop showed that the men taking part felt their knowledge of prostate cancer improved drastically, with some of them describing the workshop as an ‘eye opener’. They found the videos from survivors particularly powerful, which brought the message about prostate cancer home.

More importantly, the majority of the men who attended the workshop said they felt more confident about going to a doctor for a prostate cancer test.

Dr de Jong added: “Our PROCAN-B project aims to tackle health inequalities by raising awareness of prostate cancer in Black men, a group at higher risk, and encouraging early diagnosis.

“By involving communities directly in our work, we strive to create lasting change in health outcomes, empower communities and ensure everyone can access the information and support they need.”

The Sunderland team is working in collaboration with colleagues from Teesside University, the University of Glasgow and Middlesbrough-based Ubuntu Multicultural Centre. The Sunderland and Teesside researchers are part of Fuse, the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health.